Post by Reticulatus on Feb 26, 2012 1:54:01 GMT -5

Giant Squid - Architeuthis dux

The giant squid (genus: Architeuthis) is a deep-ocean dwelling squid in the family Architeuthidae, represented by as many as eight species. Giant squid can grow to a tremendous size (see Deep-sea gigantism): recent estimates put the maximum size at 13 metres (43 ft) for females and 10 metres (33 ft) for males from caudal fin to the tip of the two long tentacles (second only to the colossal squid at an estimated 14 metres (46 ft),one of the largest living organisms). The mantle is about 2 metres (6.6 ft) long (more for females, less for males), and the length of the squid excluding its tentacles is about 5 metres (16 ft). There have been claims of specimens measuring 20 metres (66 ft) or more, but no giant squid of such size has been scientifically documented.

On September 30, 2004, researchers from the National Science Museum of Japan and the Ogasawara Whale Watching Association took the first images of a live giant squid in its natural habitat. Several of the 556 photographs were released a year later. The same team successfully filmed a live adult giant squid for the first time on December 4, 2006.

Like all squid, a giant squid has a mantle (torso), eight arms, and two longer tentacles (the longest known tentacles of any cephalopod). The arms and tentacles account for much of the squid's great length, making giant squid much lighter than their chief predators, sperm whales. Scientifically documented specimens have masses of hundreds, rather than thousands, of kilograms.

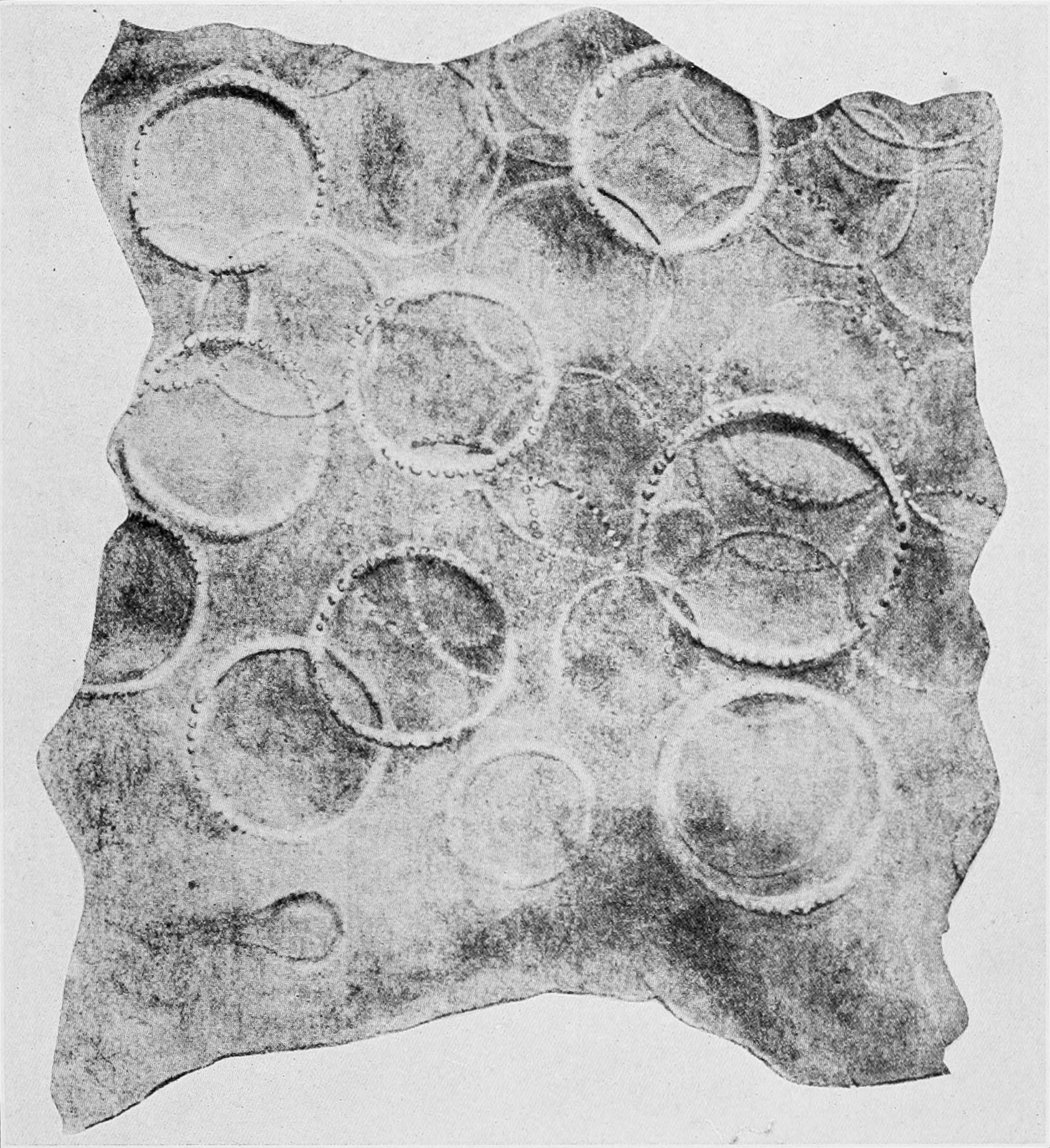

Tentacular club of Architeuthis

The inside surfaces of the arms and tentacles are lined with hundreds of sub-spherical suction cups, 2 to 5 centimetres (0.79 to 2.0 in) in diameter, each mounted on a stalk. The circumference of these suckers is lined with sharp, finely serrated rings of chitin. The perforation of these teeth and the suction of the cups serve to attach the squid to its prey. It is common to find circular scars from the suckers on or close to the head of sperm whales that have attacked giant squid. Each arm and tentacle is divided into three regions – carpus ("wrist"), manus ("hand") and dactylus ("finger"). The carpus has a dense cluster of cups, in six or seven irregular, transverse rows. The manus is broader, close to the end of the arm, and has enlarged suckers in two medial rows. The dactylus is the tip. The bases of all the arms and tentacles are arranged in a circle surrounding the animal's single parrot-like beak, as in other cephalopods.

A portion of Sperm Whale skin with giant squid sucker scars.

Giant squid have small fins at the rear of the mantle used for locomotion. Like other cephalopods, giant squid are propelled by jet – by pulling water into the mantle cavity, and pushing it through the siphon, in gentle, rhythmic pulses. They can also move quickly by expanding the cavity to fill it with water, then contracting muscles to jet water through the siphon. Giant squid breathe using two large gills inside the mantle cavity. The circulatory system is closed, which is a distinct characteristic of cephalopods. Like other squid, they contain dark ink used to deter predators.

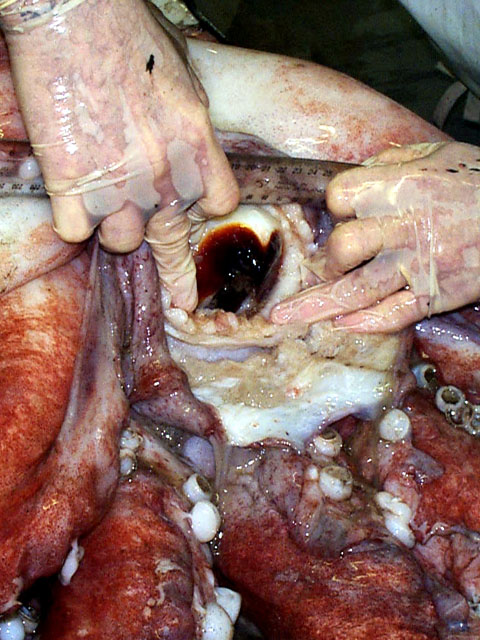

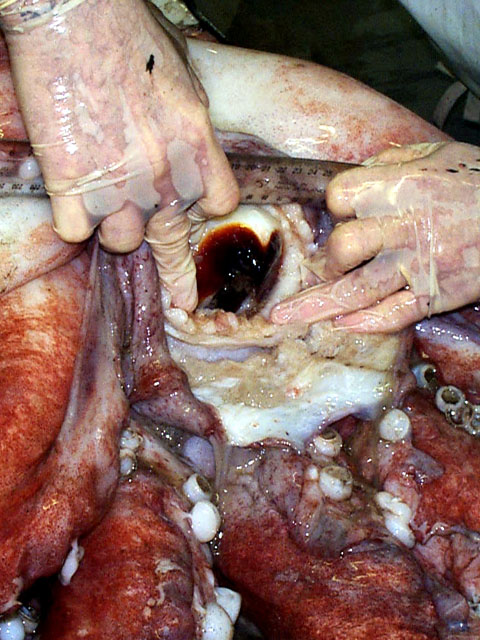

The beak of a giant squid, surrounded by the buccal mass

Giant squid have a sophisticated nervous system and complex brain, attracting great interest from scientists. They also have the largest eyes of any living creature except perhaps colossal squid – over 30 centimetres (1 ft) in diameter. Large eyes can better detect light (including bioluminescent light), which is scarce in deep water. It is thought the giant squid cannot see colour, but they can probably discern small differences in tone, which is important in the low-light conditions of the deep ocean.

Giant squid and some other large squid species maintain neutral buoyancy in seawater through an ammonium chloride solution which flows throughout their body and is lighter than seawater. This differs from the method of flotation used by fish, which involves a gas-filled swim bladder. The solution tastes somewhat like salmiakki and makes giant squid unattractive for general human consumption.

Like all cephalopods, giant squid have organs called statocysts to sense their orientation and motion in water. The age of a giant squid can be determined by "growth rings" in the statocyst's "statolith", similar to determining the age of a tree by counting its rings. Much of what is known about giant squid age is based on estimates of the growth rings and from undigested beaks found in the stomachs of sperm whales.

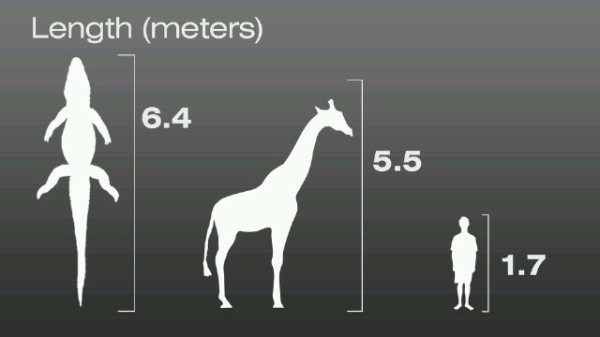

Size

The giant squid is the second largest mollusc and the second largest of all extant invertebrates. It is only exceeded by the colossal squid, Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, which may have a mantle nearly twice as long. Several extinct cephalopods, such as the Cretaceous vampyromorphid Tusoteuthis, the Cretaceous coleoid Yezoteuthis, and the Ordovician nautiloid Cameroceras may have grown even larger.

Giant squid size, particularly total length, has often been exaggerated. Reports of specimens reaching and even exceeding 20 metres (66 ft) are widespread, but no animals approaching this size have been scientifically documented. According to giant squid expert Dr. Steve O'Shea, such lengths were likely achieved by greatly stretching the two tentacles like elastic bands.

A giant squid specimen measuring over 4 metres (13 ft) without its two long feeding tentacles

Based on the examination of 130 specimens and of beaks found inside sperm whales, giant squids' mantles are not known to exceed 2.25 metres (7.4 ft). Including the head and arms, but excluding the tentacles, the length very rarely exceeds 5 metres (16 ft). Maximum total length, when measured relaxed post mortem, is estimated at 13 metres (43 ft) for females and 10 metres (33 ft) for males from caudal fin to the tip of the two long tentacles. Giant squid exhibit sexual dimorphism. Maximum weight is estimated at 275 kilograms (610 lb) for females and 150 kilograms (330 lb) for males.

Reproductive cycle

Little is known about the reproductive cycle of giant squid. It is thought that they reach sexual maturity at about 3 years; males reach sexual maturity at a smaller size than females. Females produce large quantities of eggs, sometimes more than 5 kilograms (11 lb), that average 0.5 to 1.4 millimetres (0.020 to 0.055 in) long and 0.3 to 0.7 millimetre (0.012 to 0.028 in) wide. Females have a single median ovary in the rear end of the mantle cavity and paired convoluted oviducts where mature eggs pass exiting through the oviducal glands, then through the nidamental glands. As in other squid, these glands produce a gelatinous material used to keep the eggs together once they are laid.

In males, as with most other cephalopods, the single, posterior testis produces sperm that move into a complex system of glands that manufacture the spermatophores. These are stored in the elongate sac, or Needham's sac, that terminates in the penis from which they are expelled during mating. The penis is prehensile, over 90 centimeters long, and extends from inside the mantle.

How the sperm is transferred to the egg mass is much debated, as giant squid lack the hectocotylus used for reproduction in many other cephalopods. It may be transferred in sacs of spermatophores, called spermatangia, which the male injects into the female's arms. This is suggested by a female specimen recently found in Tasmania, having a small subsidiary tendril attached to the base of each arm.

Post-larval juveniles have been discovered in surface waters off New Zealand, and there are plans to capture more and maintain them in an aquarium to learn more about the creature.

Ecology Feeding

Recent studies show that giant squid feed on deep-sea fish and other squid species. They catch prey using the two tentacles, gripping it with serrated sucker rings on the ends. Then they bring it toward the powerful beak, and shred it with the radula (tongue with small, file-like teeth) before it reaches the esophagus. They are believed to be solitary hunters, as only individual giant squid have been caught in fishing nets. Although the majority of giant squid caught by trawl in New Zealand waters have been associated with the local hoki (Macruronus novaezelandiae) fishery, hoki do not feature in the squid's diet. This suggests that giant squid and hoki prey on the same animals.

Predators

Adult giant squids' only known predators are sperm whales. It has also been suggested that pilot whales may feed on giant squid. Juveniles are preyed on by deep sea sharks and other fish. Because sperm whales are skilled at locating giant squid, scientists have tried to observe them to study the squid.

Range and habitat

Worldwide giant squid distribution based on recovered specimens.Giant squid are very widespread, occurring in all of the world's oceans. They are usually found near continental and island slopes from the North Atlantic Ocean, especially Newfoundland, Norway, the northern British Isles, Spain and the oceanic islands of the Azores and Madeira, to the South Atlantic around southern Africa, the North Pacific around Japan, and the southwestern Pacific around New Zealand and Australia. Specimens are rare in tropical and polar latitudes.

The vertical distribution of giant squid is incompletely known, but data from trawled specimens and sperm whale diving behaviour suggests it spans a large range of depths, possibly 300–1000 m

The giant squid (genus: Architeuthis) is a deep-ocean dwelling squid in the family Architeuthidae, represented by as many as eight species. Giant squid can grow to a tremendous size (see Deep-sea gigantism): recent estimates put the maximum size at 13 metres (43 ft) for females and 10 metres (33 ft) for males from caudal fin to the tip of the two long tentacles (second only to the colossal squid at an estimated 14 metres (46 ft),one of the largest living organisms). The mantle is about 2 metres (6.6 ft) long (more for females, less for males), and the length of the squid excluding its tentacles is about 5 metres (16 ft). There have been claims of specimens measuring 20 metres (66 ft) or more, but no giant squid of such size has been scientifically documented.

On September 30, 2004, researchers from the National Science Museum of Japan and the Ogasawara Whale Watching Association took the first images of a live giant squid in its natural habitat. Several of the 556 photographs were released a year later. The same team successfully filmed a live adult giant squid for the first time on December 4, 2006.

Like all squid, a giant squid has a mantle (torso), eight arms, and two longer tentacles (the longest known tentacles of any cephalopod). The arms and tentacles account for much of the squid's great length, making giant squid much lighter than their chief predators, sperm whales. Scientifically documented specimens have masses of hundreds, rather than thousands, of kilograms.

Tentacular club of Architeuthis

The inside surfaces of the arms and tentacles are lined with hundreds of sub-spherical suction cups, 2 to 5 centimetres (0.79 to 2.0 in) in diameter, each mounted on a stalk. The circumference of these suckers is lined with sharp, finely serrated rings of chitin. The perforation of these teeth and the suction of the cups serve to attach the squid to its prey. It is common to find circular scars from the suckers on or close to the head of sperm whales that have attacked giant squid. Each arm and tentacle is divided into three regions – carpus ("wrist"), manus ("hand") and dactylus ("finger"). The carpus has a dense cluster of cups, in six or seven irregular, transverse rows. The manus is broader, close to the end of the arm, and has enlarged suckers in two medial rows. The dactylus is the tip. The bases of all the arms and tentacles are arranged in a circle surrounding the animal's single parrot-like beak, as in other cephalopods.

A portion of Sperm Whale skin with giant squid sucker scars.

Giant squid have small fins at the rear of the mantle used for locomotion. Like other cephalopods, giant squid are propelled by jet – by pulling water into the mantle cavity, and pushing it through the siphon, in gentle, rhythmic pulses. They can also move quickly by expanding the cavity to fill it with water, then contracting muscles to jet water through the siphon. Giant squid breathe using two large gills inside the mantle cavity. The circulatory system is closed, which is a distinct characteristic of cephalopods. Like other squid, they contain dark ink used to deter predators.

The beak of a giant squid, surrounded by the buccal mass

Giant squid have a sophisticated nervous system and complex brain, attracting great interest from scientists. They also have the largest eyes of any living creature except perhaps colossal squid – over 30 centimetres (1 ft) in diameter. Large eyes can better detect light (including bioluminescent light), which is scarce in deep water. It is thought the giant squid cannot see colour, but they can probably discern small differences in tone, which is important in the low-light conditions of the deep ocean.

Giant squid and some other large squid species maintain neutral buoyancy in seawater through an ammonium chloride solution which flows throughout their body and is lighter than seawater. This differs from the method of flotation used by fish, which involves a gas-filled swim bladder. The solution tastes somewhat like salmiakki and makes giant squid unattractive for general human consumption.

Like all cephalopods, giant squid have organs called statocysts to sense their orientation and motion in water. The age of a giant squid can be determined by "growth rings" in the statocyst's "statolith", similar to determining the age of a tree by counting its rings. Much of what is known about giant squid age is based on estimates of the growth rings and from undigested beaks found in the stomachs of sperm whales.

Size

The giant squid is the second largest mollusc and the second largest of all extant invertebrates. It is only exceeded by the colossal squid, Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, which may have a mantle nearly twice as long. Several extinct cephalopods, such as the Cretaceous vampyromorphid Tusoteuthis, the Cretaceous coleoid Yezoteuthis, and the Ordovician nautiloid Cameroceras may have grown even larger.

Giant squid size, particularly total length, has often been exaggerated. Reports of specimens reaching and even exceeding 20 metres (66 ft) are widespread, but no animals approaching this size have been scientifically documented. According to giant squid expert Dr. Steve O'Shea, such lengths were likely achieved by greatly stretching the two tentacles like elastic bands.

A giant squid specimen measuring over 4 metres (13 ft) without its two long feeding tentacles

Based on the examination of 130 specimens and of beaks found inside sperm whales, giant squids' mantles are not known to exceed 2.25 metres (7.4 ft). Including the head and arms, but excluding the tentacles, the length very rarely exceeds 5 metres (16 ft). Maximum total length, when measured relaxed post mortem, is estimated at 13 metres (43 ft) for females and 10 metres (33 ft) for males from caudal fin to the tip of the two long tentacles. Giant squid exhibit sexual dimorphism. Maximum weight is estimated at 275 kilograms (610 lb) for females and 150 kilograms (330 lb) for males.

Reproductive cycle

Little is known about the reproductive cycle of giant squid. It is thought that they reach sexual maturity at about 3 years; males reach sexual maturity at a smaller size than females. Females produce large quantities of eggs, sometimes more than 5 kilograms (11 lb), that average 0.5 to 1.4 millimetres (0.020 to 0.055 in) long and 0.3 to 0.7 millimetre (0.012 to 0.028 in) wide. Females have a single median ovary in the rear end of the mantle cavity and paired convoluted oviducts where mature eggs pass exiting through the oviducal glands, then through the nidamental glands. As in other squid, these glands produce a gelatinous material used to keep the eggs together once they are laid.

In males, as with most other cephalopods, the single, posterior testis produces sperm that move into a complex system of glands that manufacture the spermatophores. These are stored in the elongate sac, or Needham's sac, that terminates in the penis from which they are expelled during mating. The penis is prehensile, over 90 centimeters long, and extends from inside the mantle.

How the sperm is transferred to the egg mass is much debated, as giant squid lack the hectocotylus used for reproduction in many other cephalopods. It may be transferred in sacs of spermatophores, called spermatangia, which the male injects into the female's arms. This is suggested by a female specimen recently found in Tasmania, having a small subsidiary tendril attached to the base of each arm.

Post-larval juveniles have been discovered in surface waters off New Zealand, and there are plans to capture more and maintain them in an aquarium to learn more about the creature.

Ecology Feeding

Recent studies show that giant squid feed on deep-sea fish and other squid species. They catch prey using the two tentacles, gripping it with serrated sucker rings on the ends. Then they bring it toward the powerful beak, and shred it with the radula (tongue with small, file-like teeth) before it reaches the esophagus. They are believed to be solitary hunters, as only individual giant squid have been caught in fishing nets. Although the majority of giant squid caught by trawl in New Zealand waters have been associated with the local hoki (Macruronus novaezelandiae) fishery, hoki do not feature in the squid's diet. This suggests that giant squid and hoki prey on the same animals.

Predators

Adult giant squids' only known predators are sperm whales. It has also been suggested that pilot whales may feed on giant squid. Juveniles are preyed on by deep sea sharks and other fish. Because sperm whales are skilled at locating giant squid, scientists have tried to observe them to study the squid.

Range and habitat

Worldwide giant squid distribution based on recovered specimens.Giant squid are very widespread, occurring in all of the world's oceans. They are usually found near continental and island slopes from the North Atlantic Ocean, especially Newfoundland, Norway, the northern British Isles, Spain and the oceanic islands of the Azores and Madeira, to the South Atlantic around southern Africa, the North Pacific around Japan, and the southwestern Pacific around New Zealand and Australia. Specimens are rare in tropical and polar latitudes.

The vertical distribution of giant squid is incompletely known, but data from trawled specimens and sperm whale diving behaviour suggests it spans a large range of depths, possibly 300–1000 m