Post by Venomous Dragon on Oct 18, 2011 0:11:36 GMT -5

Collared lizards

Male

Female

Collared Lizards

Collared lizards of the genus Crotaphytus are among the most colorful lizards in North America. They were first described in Edwin James' account of Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in 1823. Thomas Say, a member of that expedition, collected and described them as Agama collaris. In 1842, Holbrock placed collared lizards in the new genus Crotaphytus. Until recently, leopard lizards were included in this genus. They have since been placed in the genus Gambelia. In 1989 Frost and Etheridge put these two genera in the iguanian family Crotaphytidae. With the discovery of new species, scientific names of collared lizards have changed many times. Currently they have been divided into at least seven species. Crotaphytus reticulates is a tan to brown lizard with reticulations covering most of its dorsum, limbs, and tail. Some of these reticulations are filled with black pigmentations. Unlike the rest of Crotaphytus, there is no color difference between males and females except during the breeding season. During this time males develop a bright yellow coloration on their chest. The collars on C. reticulates are faint and the anterior collar is complete ventrally. The dewlap, or gular area is a greenish gray with black pigmentation in the center. Collared lizards have small pockets at the base of the tail and folds of skin above the front legs. Mites and chiggers gather in these areas. C. reticulates lacks post femoral mite pockets that are present in the rest of the genus. This suggest that it broke away from the group first. The inside of the mouth and throat of C. reticulates is black. Oral melanin is displayed during mouth gaping, a defense behavior. C. reticulates has black femoral pore secretions, the rest of the genus has gray secretions.

Of all the Crotaphytus species, C. reticulates is the only species that is not restricted to rocky habitat. It is native to the Tampaulipan biotic province of southern Texas and adjacent Mexico. C. reticulates spends its life on the ground much like a close relative the leopard lizard. When threatened, it will take refuge in rodent borrows and under brush. This species range is declining due to habitat destruction and possibly climate change. The reticulated collared lizard is the only Crotaphytus species that is protected from collecting. Crotaphytus collaris has the largest distribution of all the Crotaphytus species. C. collaris is the most generalized of all the collared lizards and has adapted to many different habitats. C. collaris is divided into four subspecies. The eastern collared lizard, C. c. collaris, is the most colorful of the group. It ranges from the Ozarks of southern Missouri and Arkansas, westward through the plains of Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and into eastern New Mexico. Here it comes into contact with the western collared lizard, C. c. baileyi. C. c. baileyi is similar in color to C. c. collaris. It occurs from western Arizona, eastward into central New Mexico, down the Sierre Madre Occidental into central Mexico. In western Arizona two hybrid zones have been discovered where C. c. baileyi comes into contact with C. c. bicinctores (Axtell, 1972)(Montanucci, 1983).

In southeastern Arizona, C. c. baileyi comes into contact and hybridizes with another collaris race, C. c. fuscus. C. c. fuscus ranges from south-central New Mexico, southward into northern Mexico. C. c. fuscus is a dull brown lizard that lacks the bright colors found in the rest of this species. C. c. auriceps, the yellow headed collared lizard, is found in east central Utah and western Colorado. This subspecies is similar in coloration to C. c. baileyi except the head is entirely yellow in males. It intergrades with C. c. baileyi in the four corners area.

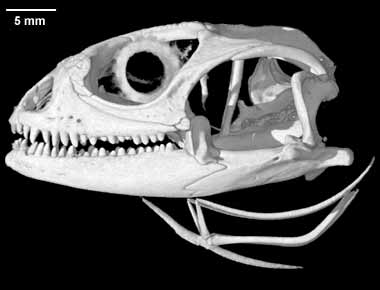

Crotaphytus collaris is characterized by a round cylindrical tail and a broad head with a blunt snout. Like C. reticulates, C. collaris has black oral melanin. Dorsal coloration varies greatly in this species. In some population it is green while in others it is blue to turquoise. C. c. fuscus lacks the greens and blues. It is brown to tan. Some males have yellow bands across the dorsum. The coloration in male collared lizards evolved as a result of their display behavior. Females are greenish to brown and are not as bright as the males. Gular coloration also varies. Some populations have green to blue dewlaps while others have yellow or orange dewlaps. This species lacks the black pigmentation in the center of its dewlap. A pair of collars are always present. In this species, the anterior collar doesn't connect in the gular area as it does in the rest of Crotaphytus. In some populations, C. collaris has black patches, inguinal patches, on its sides, in front of the rear legs. This characteristic is not fixed with this species as it is with the rest of the genus. Most of C. collaris has white spotting covering the dorsum. In the Mexican state of Coachila, where C. collaris approaches the range of C.reticulates, there is the black spotted collared lizard. It has characteristics of both species. The anterior collar is complete ventrally and it has reticulations covering the dorsum. Most of the reticulations are filled with black pigmentation. It also has green dorsal coloration and developed collars. An active hybrid zone hasn't been found, so the origin of these lizards needs further study.

Crotaphytus nebrius, the Sonoran collared lizard, is often considered a subspecies of C. collaris. It shares many characteristics from both the collaris and the insularis groups. In the early 1970's, Axtell believed that C. nebrius was an intergrade between C. collaris and C. dickersonae in the Guayamas, Mexico area. They occur on parallel mountain ranges there but do not intergrade. C. nebrius has tan to yellow dorsal coloration with white spotting on the back and sides. These spots are generally larger than the white spots found on C. collaris. This species lacks the blues and greens found in C. collaris. The gular area is gray to brown and oral melanin is present. Both collars are present with the anterior collar complete ventrally. Inguinal patches are fixed in this species.

C. nebrius inhabits most of Sonora Mexico. It crosses into the United States on the north to south trending mountain ranges in southwestern Arizona. The Gila River prevents contact between this species and C. bicinctores. Since there are no mountains reaching up from Sonora to the Gila River near the Sentinel Plain, C. nebrius isn't found there. This is the only place where C. bicinctores has become established south of the river. Crotaphytus dickersonae has a very small range in the coastal mountains of Sonora, Mexico, between Punta Cirio and Bahia Kino. It is also found on the Isla Tiburon in the Sea of Cortez. This lizard has many characteristics of the collaris and the insularis groups. Its ancestors may have been hybrids of both forms. The dorsal coloration is a vibrant cobalt blue without any yellow as in C. collaris. The dorsum is covered with white spots and the collars are complete dorsally. The anterior collar is complete ventrally. The gular area is gray with a black center. Oral melanin and enlarged inguinal patches are present. The body shape of C. dickersonae is like the insularis form. Males have a laterally compressed tail and an elongated snout. Montanucci, Axtell, and Dessauer found that genetically, C. dickersonae is more similar to C. collaris than it is to the insularis group. More study is needed to find the origin of this beautiful species. Crotaphytus insularis, the baja collared lizard, occurs on the eastern escarpment of the peninsular mountains of southern California, southward to the Sierra San Pedro Martir of Baja Mexico. In the southern portion of its range, it can be found on both sides of the peninsula. It also occurs on the Isla de la Guardia in the Sea of Cortez. The lizards on this island were recognized as a separate species. During the one million years that these lizards have been separated, there is no genetic difference between the two (McGuire, 1994). They can be separated into two subspecies. C. insularis vestigium on the baja peninsula and C. insularis insularis occurring on Isla de la Guardia.

These lizards have an elongated snout. Males have laterally compressed tails and enlarged inguinal patches. McGuire theorizes that the elongated snout found in the insularis group and C. dickersonae, could have evolved to help catch vertebrate prey such lizards. The compressed tail and inguinal patches are believed to be male display features. A laterally compressed tail makes the lizard appear larger. C. insularis lacks the oral melanin and doesn't gape its mouth as a defense reaction. The collars of C. insularis do not connect mid-dorsally. In some individuals the posterior collar is faint or nonexistent. It appears that collar reduction is going on in this species. The anterior collar is complete ventrally. In males the gular coloration is gray with a dark center. Females usually have a yellow gular area without the dark center. The dorsum is olive gray to tan with white dashes, spots, and bars. In C. i. vestigium the bars are often wavy and sometimes offset mid-dorsally. In C. i. insularis these bars are reduced or absent.

Often referred to as the Mojave or Great Basin collared lizard, Crotaphytus bicinctores has the largest range of the insularis group. It occurs from southern Idaho and Oregon, southward through Nevada and western Utah, to the deserts of western Arizona and California. C. bicinctores intergrades with C. collaris baileyi in northwestern Arizona and comes into contact with, but doesn't intergrade with C. nebrius along the Gila River in southeastern Arizona. In southern California C. bicinctores is separated from C. i. vestigium by the San Gorgonio pass. There is no evidence of integration between these two species (Sanborn and Loomis, 1979). C. bicinctores is a brown lizard with small white spots on the dorsum. Males have orange bars across their back and their dewlap is bluish with a black center. The collars are complete or nearly complete mid-dorsally. The anterior collar is complete ventrally. As with the rest of the insularis group, males have elongated snouts, laterally compressed tails, and large inguinal patches. It also lacks oral melanin. Crotaphytus grismeri is a species described by McGuire in 1994. It is a brown lizard with white spotting much like C. bicinctores. Males lack the orange body bars found in C. bicinctores. The collars are complete or nearly complete mid-dorsally and the anterior collar is complete ventrally in the gular area. There is green pigmentation on the white bars between the collars. The gular area is bluish gray with a black center. This species lacks oral melanin. Like the rest of the insularis group, males have an elongated snout, laterally compressed tail, and enlarged inguinal patches. Axtell suggested that these characteristics were primitive character states. Subadult females have a burnt orange tail, which is not found in the rest of Crotaphytus. C. grismeri inhabits the Sierra de Las Cucapas and Sierra el Major mountains in northern Baja Mexico. These lizards appear to be sister taxon to C. bicinctores but as with the rest of Crotaphytus further study is needed. The speciation of Crotaphytus is directly related to plate tectonics and the formation of mountain ranges.

Ancestral collared lizards probably evolved during the Miocene epoch. During this time, there was a north to south trending volcanic arc extending along the west coast of North America. From 20 to 12 million years ago the Baja peninsula was a part of mainland Mexico. Underlying forces responsible for the basin and range topography of western North America, formed a deep basin where the Pacific plate once sub ducted beneath the North American plate. About 13 million years ago, the ocean invaded this basin. By 6 million years ago, it had reached the San Gorgonio pass area near Palm Springs, California. These events probably separated ancestral C. dickersonae from ancestral C. collaris. Ancestral C. collaris or C. nebrius was already established in the Sierra Madre Occidental. It is not known if there was suitable habitat in this basin for C. dickersonae to cross over to the volcanic arc or if the lizards dispersed over water as the ocean invaded. In any case, ancestral C. dickersonae became isolated on this arc. Around 5.5 million years ago, the former zone began to split as a transform fault developed. This split the volcanic arc, leaving parts of it on the North American plate and parts of it on the Pacific plate. A spreading center developed and the Baja peninsula began on its northwestern journey. This left ancestors to the insular stock on the peninsula. It is probable that as Baja broke away, C. bicinctores and C. grismeri dispersed to their present locations. Since the gulf was present during this time, these lizards most likely crossed over water. There is evidence that the Sierra de Las Cucapas and Sierra el Mayor mountains existed as a Pliocene island (Gastil, 1983). Chuckwallas and collared lizards are the only saxicolous reptiles found on these mountains. Both are well suited for overwater dispersal (Grismer, 1994). As the peninsula drifted away from the mainland, C. insularis evolved on this narrow mountain block. Around 1 million years ago, the axis of the spreading center shifted from the east side of Isla de la Guardia to the west side of the island. This event displaced the island 20 kilometers to the east (Phillips, 1968). C. insularis either went with this island or dispersed over water to the island (McGuire, 1994).

On the eastern side of the Sierra Madre Occidental, C. reticulates probably broke away from the ancestral C. collaris before C. dickersonae did. Mountain building activity may not have played an important role in C. reticulates' divergence, since it is not restricted to rocky habitat. Changes in the climate may have been the separating factor. C. reticulates prefers a slightly wetter climate than the xeric condition preferred by C. collaris. Between 2000 and 4000 years ago, the climate became drier and this may have caused C. reticulates to retreat eastward. C. reticulates may have left scattered populations behind which were absorbed by C. collaris as it moved into the area. This could explain the origin of the black spotted collared lizards that occur between the present day ranges of C. collaris and C. reticulates (Montanucci, 1974).

Collared lizards emerge from hibernation during March and April. Follicular development has begun in females by early April (Ferguson, 1976). Orange to red bars and spots appear on her neck and sides. This

coloration, which can appear overnight, is visual signal to the male lizards that the females are ready to mate. Around the same time, testes size in male lizards increases and continues to increase until early June (Trauth, 1979).

Collared lizards are very territorial. Male lizards defend 2 or 3 female lizards that share his territory. If a male lizard enters another males territory, the defending male arches its back, compress its sides in an attempt to appear large and fierce. He will then do a series of pushups. C. collaris ' pushups are so powerful that its front feet often come off the ground. If this doesn't deter the trespasser, the defending male chases the intruder off. Male lizards will approach a female and do a series of head bobs. The lizards circle each other, both of them bobbing their heads. The male will grab the female by the back of her neck and attempt to mate. The female becomes submissive if she is ready. If she is not ready or already gravid, she will twist her body and roll him off. Sometimes the female lizard climbs on the males back to subdue his advances.

The breeding season last until June. Once the eggs are laid, female lizards aggressively defend the nesting site. Her breeding coloration also fades. This coloration becomes vibrant again if there is another clutch. In the northern part of their range, female collared lizards produce only one clutch. In the south, they often produce two to four clutches. Clutch size ranges from one to thirteen. There is a positive correlation between body size and clutch size (Ballinger and Hipp, 1985). The average clutch size is about six. Eggs are usually deposited under rocks and will hatch in about 40 to 60 days.

Hatchlings appear from July to September. By late August to early September, adult lizards usually start their hibernation. This leaves the hatchlings with less competition. The young lizards eat anything that it can get their mouth around. This insures survival over the winter. Young male lizards often have orange bars across their dorsum similar to breeding females. This is to deter adult male aggression until the young lizard can find its own territory. Collard lizard are usually sexually mature during their first spring. Lizards from colder areas may not reproduce until their second season. Males reach their maximum size by the age of three. Females continue to grow very slowly their entire lives (Sexton, Andrews, and Bramble, 1992).

Collared lizards emerge each morning around 9 to 10 a.m. to bask on prominent rocks in their territory. Once they reach their preferred body temperature, they begin to forage for insects. They are very agile and can easily snag flying insects out of midair. Before rushing down on their prey they will often do a series of tail wags. Collared lizards occasionally feed on plant matter and vertebrate prey. Collared lizards have excellent eyesight and are difficult to approach. The best way to get close, is to scan boulders far ahead of you with binoculars. The lizards are usually already looking back at you by the time you spot them. When approaching these lizards, do so very slowly. You can get within a few feet if you move slow and don't startle them. If you get too close they'll dash under rocks, often running on their hind legs. Their tails are used to balance when running bipedally and it doesn't break off easily like most other lizards. It will only grow back if just the tip is broken off . When hiding under rocks or sleeping, they will coil their tail to keep from being pulled out by it. These lizards are very aggressive when corned. They will hiss and leap at you in an attempt to bite. Once they get a hold of you, they often hold on.

Collared lizards make excellent captives as long as their basic requirements are met. These lizards are very active and you can not give them enough room. Adult lizards should be kept in at least a forty gallon aquarium. These lizards are very territorial, no more than one male and two females should be kept together. Sand makes an excellent substrate. Collared lizards are saxicolous so rocks piles make natural basking sites. If more than one lizard is to be caged together, make several basking sites. Be careful that the rocks can not come down on the lizards when they dig around them. Like most lizards, collared lizards require ultraviolet light. Use a full-spectrum fluorescent bulb along with a incandescent bulb above the basking site. For healthy and colorful lizards, natural sunlight is a must. Collared lizards like it hot. Their basking site should be between 100 and 105 degrees. The rest of their cage should be in the high 80's to 90's during the day. Some individuals will drink from a water bowl, but most will only drink from water droplets. Mist the rocks and glass in their enclosure to stimulate drinking every few days. Collared lizards eat a lot and can be fed daily. Crickets are the most convenient food source available. It is best to feed them a variety of insects. It is always fun to watch them catch flying insects in midair. Some individuals will also eat lizards and pinkies.

Captive bred lizards do excellent as captives. Wild caught lizards don't always do as well. Many die from the stress of being taken from their natural environment. They are usually loaded ticks, chiggers, nematodes, and other parasites. Wild caught lizards will often rub their nose raw trying to escape. If the lizard doesn't adapt, it

will go off feed until it is too weak to move. It will lose weight and wither away over a period of several weeks. Once this has started, it is almost impossible to turn them around. Collared lizards are fairly easy to breed in captivity. They must hibernate at least a month and can be left in this state for several months. Two weeks before hibernation, stop feeding them so their stomachs will be empty. Turn off the heat sources and slowly cool the lizards down to between 40 to 55 degrees. If your room doesn't stay cool enough to induce hibernation, you can hibernate them in the refrigerator. Use a thermometer to regulate the temperature. Because the refrigerator will dehydrate the lizards, I put them in plastic shoe boxes with damp sand as a substrate. I also keep a small bowl of water in with them. Check them every few days and mist the sand down as it dries.

After hibernation, slowly warm the lizards up by keeping them at room temperature for a day or so, then you can turn up the heat. Start feeding the lizards insects dusted with calcium. The females will especially need it for strong egg development. Within a few weeks the female lizards will develop their breeding coloration.

After the lizards have mated, the female will start to show bulges near its abdomen. At this time, keep a moist spot in the cage and the female will usually lay the eggs in this spot. When she is ready to lay the eggs, she will begin digging. Check her daily, because she will appear skinny after she has deposited the eggs. The eggs must be removed from the cage. Keep them right side up and place them in an incubator. An incubator can be made from a plastic shoe box with a hole, the size of a quarter, cut in the top for air circulation. Fill the shoe box with about three inches of vermiculite and keep the vermiculite moist but not wet. Put the shoe box in a place were the temperature wont drop below the high 70's and won't rise above the low 90's. Temperature fluctuations will insure that the hatchlings will be of both sexes.

As long as the eggs continue to grow they should be fine, even if they turn an off white to brown. In about 40 to 60 days the eggs should be ready to hatch. It take several hours to more than a day for the hatchling to break free from their eggs. Their umbilical cords will remain attached for several days. Hatchling lizards need natural sunlight in order to develop properly. Without it, they will likely perish. They can be fed week old crickets, but they will eat anything they can get their mouths around. Collared lizards grow very fast and within a matter of weeks they can be fed adult crickets.

There are still many questions about the origin of the collared lizards. This genus should continue to be studied in the lab and in the field. Due to their beautiful colors, individual patterns, and relative tameness; collard lizards will remain popular captives. I welcome any information or questions concerning the genusCrotaphytus.

Male

Female

Collared Lizards

Collared lizards of the genus Crotaphytus are among the most colorful lizards in North America. They were first described in Edwin James' account of Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in 1823. Thomas Say, a member of that expedition, collected and described them as Agama collaris. In 1842, Holbrock placed collared lizards in the new genus Crotaphytus. Until recently, leopard lizards were included in this genus. They have since been placed in the genus Gambelia. In 1989 Frost and Etheridge put these two genera in the iguanian family Crotaphytidae. With the discovery of new species, scientific names of collared lizards have changed many times. Currently they have been divided into at least seven species. Crotaphytus reticulates is a tan to brown lizard with reticulations covering most of its dorsum, limbs, and tail. Some of these reticulations are filled with black pigmentations. Unlike the rest of Crotaphytus, there is no color difference between males and females except during the breeding season. During this time males develop a bright yellow coloration on their chest. The collars on C. reticulates are faint and the anterior collar is complete ventrally. The dewlap, or gular area is a greenish gray with black pigmentation in the center. Collared lizards have small pockets at the base of the tail and folds of skin above the front legs. Mites and chiggers gather in these areas. C. reticulates lacks post femoral mite pockets that are present in the rest of the genus. This suggest that it broke away from the group first. The inside of the mouth and throat of C. reticulates is black. Oral melanin is displayed during mouth gaping, a defense behavior. C. reticulates has black femoral pore secretions, the rest of the genus has gray secretions.

Of all the Crotaphytus species, C. reticulates is the only species that is not restricted to rocky habitat. It is native to the Tampaulipan biotic province of southern Texas and adjacent Mexico. C. reticulates spends its life on the ground much like a close relative the leopard lizard. When threatened, it will take refuge in rodent borrows and under brush. This species range is declining due to habitat destruction and possibly climate change. The reticulated collared lizard is the only Crotaphytus species that is protected from collecting. Crotaphytus collaris has the largest distribution of all the Crotaphytus species. C. collaris is the most generalized of all the collared lizards and has adapted to many different habitats. C. collaris is divided into four subspecies. The eastern collared lizard, C. c. collaris, is the most colorful of the group. It ranges from the Ozarks of southern Missouri and Arkansas, westward through the plains of Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and into eastern New Mexico. Here it comes into contact with the western collared lizard, C. c. baileyi. C. c. baileyi is similar in color to C. c. collaris. It occurs from western Arizona, eastward into central New Mexico, down the Sierre Madre Occidental into central Mexico. In western Arizona two hybrid zones have been discovered where C. c. baileyi comes into contact with C. c. bicinctores (Axtell, 1972)(Montanucci, 1983).

In southeastern Arizona, C. c. baileyi comes into contact and hybridizes with another collaris race, C. c. fuscus. C. c. fuscus ranges from south-central New Mexico, southward into northern Mexico. C. c. fuscus is a dull brown lizard that lacks the bright colors found in the rest of this species. C. c. auriceps, the yellow headed collared lizard, is found in east central Utah and western Colorado. This subspecies is similar in coloration to C. c. baileyi except the head is entirely yellow in males. It intergrades with C. c. baileyi in the four corners area.

Crotaphytus collaris is characterized by a round cylindrical tail and a broad head with a blunt snout. Like C. reticulates, C. collaris has black oral melanin. Dorsal coloration varies greatly in this species. In some population it is green while in others it is blue to turquoise. C. c. fuscus lacks the greens and blues. It is brown to tan. Some males have yellow bands across the dorsum. The coloration in male collared lizards evolved as a result of their display behavior. Females are greenish to brown and are not as bright as the males. Gular coloration also varies. Some populations have green to blue dewlaps while others have yellow or orange dewlaps. This species lacks the black pigmentation in the center of its dewlap. A pair of collars are always present. In this species, the anterior collar doesn't connect in the gular area as it does in the rest of Crotaphytus. In some populations, C. collaris has black patches, inguinal patches, on its sides, in front of the rear legs. This characteristic is not fixed with this species as it is with the rest of the genus. Most of C. collaris has white spotting covering the dorsum. In the Mexican state of Coachila, where C. collaris approaches the range of C.reticulates, there is the black spotted collared lizard. It has characteristics of both species. The anterior collar is complete ventrally and it has reticulations covering the dorsum. Most of the reticulations are filled with black pigmentation. It also has green dorsal coloration and developed collars. An active hybrid zone hasn't been found, so the origin of these lizards needs further study.

Crotaphytus nebrius, the Sonoran collared lizard, is often considered a subspecies of C. collaris. It shares many characteristics from both the collaris and the insularis groups. In the early 1970's, Axtell believed that C. nebrius was an intergrade between C. collaris and C. dickersonae in the Guayamas, Mexico area. They occur on parallel mountain ranges there but do not intergrade. C. nebrius has tan to yellow dorsal coloration with white spotting on the back and sides. These spots are generally larger than the white spots found on C. collaris. This species lacks the blues and greens found in C. collaris. The gular area is gray to brown and oral melanin is present. Both collars are present with the anterior collar complete ventrally. Inguinal patches are fixed in this species.

C. nebrius inhabits most of Sonora Mexico. It crosses into the United States on the north to south trending mountain ranges in southwestern Arizona. The Gila River prevents contact between this species and C. bicinctores. Since there are no mountains reaching up from Sonora to the Gila River near the Sentinel Plain, C. nebrius isn't found there. This is the only place where C. bicinctores has become established south of the river. Crotaphytus dickersonae has a very small range in the coastal mountains of Sonora, Mexico, between Punta Cirio and Bahia Kino. It is also found on the Isla Tiburon in the Sea of Cortez. This lizard has many characteristics of the collaris and the insularis groups. Its ancestors may have been hybrids of both forms. The dorsal coloration is a vibrant cobalt blue without any yellow as in C. collaris. The dorsum is covered with white spots and the collars are complete dorsally. The anterior collar is complete ventrally. The gular area is gray with a black center. Oral melanin and enlarged inguinal patches are present. The body shape of C. dickersonae is like the insularis form. Males have a laterally compressed tail and an elongated snout. Montanucci, Axtell, and Dessauer found that genetically, C. dickersonae is more similar to C. collaris than it is to the insularis group. More study is needed to find the origin of this beautiful species. Crotaphytus insularis, the baja collared lizard, occurs on the eastern escarpment of the peninsular mountains of southern California, southward to the Sierra San Pedro Martir of Baja Mexico. In the southern portion of its range, it can be found on both sides of the peninsula. It also occurs on the Isla de la Guardia in the Sea of Cortez. The lizards on this island were recognized as a separate species. During the one million years that these lizards have been separated, there is no genetic difference between the two (McGuire, 1994). They can be separated into two subspecies. C. insularis vestigium on the baja peninsula and C. insularis insularis occurring on Isla de la Guardia.

These lizards have an elongated snout. Males have laterally compressed tails and enlarged inguinal patches. McGuire theorizes that the elongated snout found in the insularis group and C. dickersonae, could have evolved to help catch vertebrate prey such lizards. The compressed tail and inguinal patches are believed to be male display features. A laterally compressed tail makes the lizard appear larger. C. insularis lacks the oral melanin and doesn't gape its mouth as a defense reaction. The collars of C. insularis do not connect mid-dorsally. In some individuals the posterior collar is faint or nonexistent. It appears that collar reduction is going on in this species. The anterior collar is complete ventrally. In males the gular coloration is gray with a dark center. Females usually have a yellow gular area without the dark center. The dorsum is olive gray to tan with white dashes, spots, and bars. In C. i. vestigium the bars are often wavy and sometimes offset mid-dorsally. In C. i. insularis these bars are reduced or absent.

Often referred to as the Mojave or Great Basin collared lizard, Crotaphytus bicinctores has the largest range of the insularis group. It occurs from southern Idaho and Oregon, southward through Nevada and western Utah, to the deserts of western Arizona and California. C. bicinctores intergrades with C. collaris baileyi in northwestern Arizona and comes into contact with, but doesn't intergrade with C. nebrius along the Gila River in southeastern Arizona. In southern California C. bicinctores is separated from C. i. vestigium by the San Gorgonio pass. There is no evidence of integration between these two species (Sanborn and Loomis, 1979). C. bicinctores is a brown lizard with small white spots on the dorsum. Males have orange bars across their back and their dewlap is bluish with a black center. The collars are complete or nearly complete mid-dorsally. The anterior collar is complete ventrally. As with the rest of the insularis group, males have elongated snouts, laterally compressed tails, and large inguinal patches. It also lacks oral melanin. Crotaphytus grismeri is a species described by McGuire in 1994. It is a brown lizard with white spotting much like C. bicinctores. Males lack the orange body bars found in C. bicinctores. The collars are complete or nearly complete mid-dorsally and the anterior collar is complete ventrally in the gular area. There is green pigmentation on the white bars between the collars. The gular area is bluish gray with a black center. This species lacks oral melanin. Like the rest of the insularis group, males have an elongated snout, laterally compressed tail, and enlarged inguinal patches. Axtell suggested that these characteristics were primitive character states. Subadult females have a burnt orange tail, which is not found in the rest of Crotaphytus. C. grismeri inhabits the Sierra de Las Cucapas and Sierra el Major mountains in northern Baja Mexico. These lizards appear to be sister taxon to C. bicinctores but as with the rest of Crotaphytus further study is needed. The speciation of Crotaphytus is directly related to plate tectonics and the formation of mountain ranges.

Ancestral collared lizards probably evolved during the Miocene epoch. During this time, there was a north to south trending volcanic arc extending along the west coast of North America. From 20 to 12 million years ago the Baja peninsula was a part of mainland Mexico. Underlying forces responsible for the basin and range topography of western North America, formed a deep basin where the Pacific plate once sub ducted beneath the North American plate. About 13 million years ago, the ocean invaded this basin. By 6 million years ago, it had reached the San Gorgonio pass area near Palm Springs, California. These events probably separated ancestral C. dickersonae from ancestral C. collaris. Ancestral C. collaris or C. nebrius was already established in the Sierra Madre Occidental. It is not known if there was suitable habitat in this basin for C. dickersonae to cross over to the volcanic arc or if the lizards dispersed over water as the ocean invaded. In any case, ancestral C. dickersonae became isolated on this arc. Around 5.5 million years ago, the former zone began to split as a transform fault developed. This split the volcanic arc, leaving parts of it on the North American plate and parts of it on the Pacific plate. A spreading center developed and the Baja peninsula began on its northwestern journey. This left ancestors to the insular stock on the peninsula. It is probable that as Baja broke away, C. bicinctores and C. grismeri dispersed to their present locations. Since the gulf was present during this time, these lizards most likely crossed over water. There is evidence that the Sierra de Las Cucapas and Sierra el Mayor mountains existed as a Pliocene island (Gastil, 1983). Chuckwallas and collared lizards are the only saxicolous reptiles found on these mountains. Both are well suited for overwater dispersal (Grismer, 1994). As the peninsula drifted away from the mainland, C. insularis evolved on this narrow mountain block. Around 1 million years ago, the axis of the spreading center shifted from the east side of Isla de la Guardia to the west side of the island. This event displaced the island 20 kilometers to the east (Phillips, 1968). C. insularis either went with this island or dispersed over water to the island (McGuire, 1994).

On the eastern side of the Sierra Madre Occidental, C. reticulates probably broke away from the ancestral C. collaris before C. dickersonae did. Mountain building activity may not have played an important role in C. reticulates' divergence, since it is not restricted to rocky habitat. Changes in the climate may have been the separating factor. C. reticulates prefers a slightly wetter climate than the xeric condition preferred by C. collaris. Between 2000 and 4000 years ago, the climate became drier and this may have caused C. reticulates to retreat eastward. C. reticulates may have left scattered populations behind which were absorbed by C. collaris as it moved into the area. This could explain the origin of the black spotted collared lizards that occur between the present day ranges of C. collaris and C. reticulates (Montanucci, 1974).

Collared lizards emerge from hibernation during March and April. Follicular development has begun in females by early April (Ferguson, 1976). Orange to red bars and spots appear on her neck and sides. This

coloration, which can appear overnight, is visual signal to the male lizards that the females are ready to mate. Around the same time, testes size in male lizards increases and continues to increase until early June (Trauth, 1979).

Collared lizards are very territorial. Male lizards defend 2 or 3 female lizards that share his territory. If a male lizard enters another males territory, the defending male arches its back, compress its sides in an attempt to appear large and fierce. He will then do a series of pushups. C. collaris ' pushups are so powerful that its front feet often come off the ground. If this doesn't deter the trespasser, the defending male chases the intruder off. Male lizards will approach a female and do a series of head bobs. The lizards circle each other, both of them bobbing their heads. The male will grab the female by the back of her neck and attempt to mate. The female becomes submissive if she is ready. If she is not ready or already gravid, she will twist her body and roll him off. Sometimes the female lizard climbs on the males back to subdue his advances.

The breeding season last until June. Once the eggs are laid, female lizards aggressively defend the nesting site. Her breeding coloration also fades. This coloration becomes vibrant again if there is another clutch. In the northern part of their range, female collared lizards produce only one clutch. In the south, they often produce two to four clutches. Clutch size ranges from one to thirteen. There is a positive correlation between body size and clutch size (Ballinger and Hipp, 1985). The average clutch size is about six. Eggs are usually deposited under rocks and will hatch in about 40 to 60 days.

Hatchlings appear from July to September. By late August to early September, adult lizards usually start their hibernation. This leaves the hatchlings with less competition. The young lizards eat anything that it can get their mouth around. This insures survival over the winter. Young male lizards often have orange bars across their dorsum similar to breeding females. This is to deter adult male aggression until the young lizard can find its own territory. Collard lizard are usually sexually mature during their first spring. Lizards from colder areas may not reproduce until their second season. Males reach their maximum size by the age of three. Females continue to grow very slowly their entire lives (Sexton, Andrews, and Bramble, 1992).

Collared lizards emerge each morning around 9 to 10 a.m. to bask on prominent rocks in their territory. Once they reach their preferred body temperature, they begin to forage for insects. They are very agile and can easily snag flying insects out of midair. Before rushing down on their prey they will often do a series of tail wags. Collared lizards occasionally feed on plant matter and vertebrate prey. Collared lizards have excellent eyesight and are difficult to approach. The best way to get close, is to scan boulders far ahead of you with binoculars. The lizards are usually already looking back at you by the time you spot them. When approaching these lizards, do so very slowly. You can get within a few feet if you move slow and don't startle them. If you get too close they'll dash under rocks, often running on their hind legs. Their tails are used to balance when running bipedally and it doesn't break off easily like most other lizards. It will only grow back if just the tip is broken off . When hiding under rocks or sleeping, they will coil their tail to keep from being pulled out by it. These lizards are very aggressive when corned. They will hiss and leap at you in an attempt to bite. Once they get a hold of you, they often hold on.

Collared lizards make excellent captives as long as their basic requirements are met. These lizards are very active and you can not give them enough room. Adult lizards should be kept in at least a forty gallon aquarium. These lizards are very territorial, no more than one male and two females should be kept together. Sand makes an excellent substrate. Collared lizards are saxicolous so rocks piles make natural basking sites. If more than one lizard is to be caged together, make several basking sites. Be careful that the rocks can not come down on the lizards when they dig around them. Like most lizards, collared lizards require ultraviolet light. Use a full-spectrum fluorescent bulb along with a incandescent bulb above the basking site. For healthy and colorful lizards, natural sunlight is a must. Collared lizards like it hot. Their basking site should be between 100 and 105 degrees. The rest of their cage should be in the high 80's to 90's during the day. Some individuals will drink from a water bowl, but most will only drink from water droplets. Mist the rocks and glass in their enclosure to stimulate drinking every few days. Collared lizards eat a lot and can be fed daily. Crickets are the most convenient food source available. It is best to feed them a variety of insects. It is always fun to watch them catch flying insects in midair. Some individuals will also eat lizards and pinkies.

Captive bred lizards do excellent as captives. Wild caught lizards don't always do as well. Many die from the stress of being taken from their natural environment. They are usually loaded ticks, chiggers, nematodes, and other parasites. Wild caught lizards will often rub their nose raw trying to escape. If the lizard doesn't adapt, it

will go off feed until it is too weak to move. It will lose weight and wither away over a period of several weeks. Once this has started, it is almost impossible to turn them around. Collared lizards are fairly easy to breed in captivity. They must hibernate at least a month and can be left in this state for several months. Two weeks before hibernation, stop feeding them so their stomachs will be empty. Turn off the heat sources and slowly cool the lizards down to between 40 to 55 degrees. If your room doesn't stay cool enough to induce hibernation, you can hibernate them in the refrigerator. Use a thermometer to regulate the temperature. Because the refrigerator will dehydrate the lizards, I put them in plastic shoe boxes with damp sand as a substrate. I also keep a small bowl of water in with them. Check them every few days and mist the sand down as it dries.

After hibernation, slowly warm the lizards up by keeping them at room temperature for a day or so, then you can turn up the heat. Start feeding the lizards insects dusted with calcium. The females will especially need it for strong egg development. Within a few weeks the female lizards will develop their breeding coloration.

After the lizards have mated, the female will start to show bulges near its abdomen. At this time, keep a moist spot in the cage and the female will usually lay the eggs in this spot. When she is ready to lay the eggs, she will begin digging. Check her daily, because she will appear skinny after she has deposited the eggs. The eggs must be removed from the cage. Keep them right side up and place them in an incubator. An incubator can be made from a plastic shoe box with a hole, the size of a quarter, cut in the top for air circulation. Fill the shoe box with about three inches of vermiculite and keep the vermiculite moist but not wet. Put the shoe box in a place were the temperature wont drop below the high 70's and won't rise above the low 90's. Temperature fluctuations will insure that the hatchlings will be of both sexes.

As long as the eggs continue to grow they should be fine, even if they turn an off white to brown. In about 40 to 60 days the eggs should be ready to hatch. It take several hours to more than a day for the hatchling to break free from their eggs. Their umbilical cords will remain attached for several days. Hatchling lizards need natural sunlight in order to develop properly. Without it, they will likely perish. They can be fed week old crickets, but they will eat anything they can get their mouths around. Collared lizards grow very fast and within a matter of weeks they can be fed adult crickets.

There are still many questions about the origin of the collared lizards. This genus should continue to be studied in the lab and in the field. Due to their beautiful colors, individual patterns, and relative tameness; collard lizards will remain popular captives. I welcome any information or questions concerning the genusCrotaphytus.